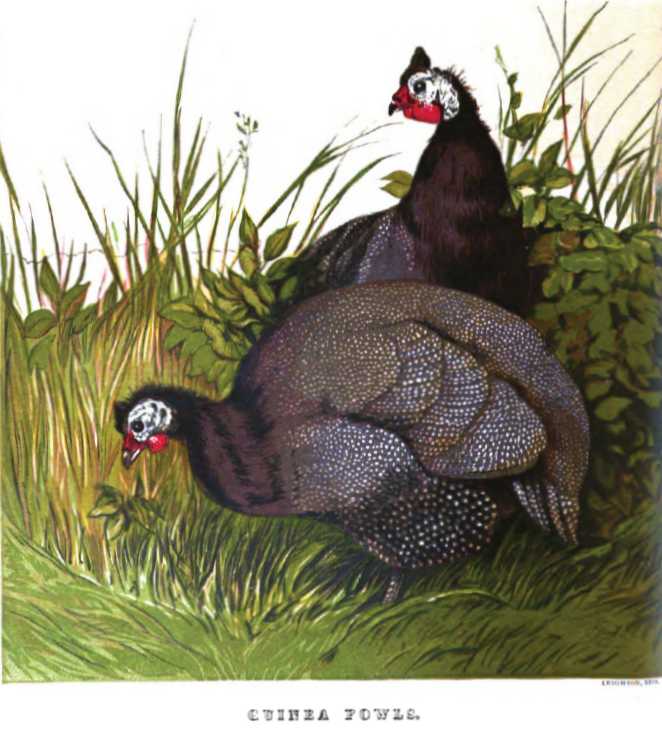

From The Poultry Book 1867

The Guinea Fowl

Guinea fowls, of which there are eight distinct species at present known to naturalists, are all natives of the African continent, or of the adjacent Island of Madagascar.

They constitute the genus Numida, of which the West African wild species, N. Meleagris, is generally regarded as the origin of our domestic breed.

This bird is found wild in Western Africa, extending from the Gambia southwards, through Ashantee to the Gaboon; it is also said to exist in the Cape de Verd Islands.

Naturalists, however, incline to the belief that the East African, or, as it is generally termed, the Abyssinian Guinea fowl, N. ptiloryncha, found in Kordossan, Abyssinia, and Sennaar, is more likely to be the one to which we are indebted for this addition to our comparatively meagre stock of domesticated animals.

As the Guinea fowl was well known to the Romans, and bore a high value at the public and private feasts at the time when the luxury of the empire was at its greatest height, this idea is exceedingly probable.

The Romans held comparatively little intercourse with South Western Africa, but were so situated as to receive birds from the eastern part of the continent through Egypt, with which country they had constant intercourse.

Of the habits of these two species in their wild state on the African continent, but little is known; but the Guinea-fowl was introduced into the warm and genial climate of Jamaica, which closely resembles its own, nearly 200 years since; there it soon became wild, and was described as wild game 150 years ago.

Guinea Fowl in Jamaica

We may therefore avail ourselves of Mr. Gosse’s description of its habits in that island, as being nearly identical with those of the birds in their native habitats.

We may therefore avail ourselves of Mr. Gosse’s description of its habits in that island, as being nearly identical with those of the birds in their native habitats.

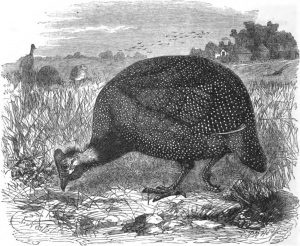

“The Guinea-fowl,” writes the author of the Birds of Jamaica, ” makes itself too familiar to the settlers by its depredations in the provision grounds.

“In the cooler months of the year, they come in numerous coveys from the woods, and scattering themselves in the grounds at early dawn, scratch up the yams and cocoes. A large hole is dug by their vigorous feet in a very short time, and the tubers exposed, which are then pecked away, so as to be almost destroyed, and quite spoiled.

“A little later, when the planting season begins, they do still greater damage by digging up and devouring the seed-yams and cocoe-heads, thus frustrating the hopes of the husbandman in the bud. The corn is no sooner put into the ground than it is scratched out; and the peas are not only dug up by them, but shelled in the pod.

“The sweet potato, however, as I am informed, escapes their ravages, being invariably rejected by them. To protect the growing provisions, some of the negro peasants have recourse to scarecrows, and others endeavour to capture the birds by a common rat-gin set in their way. It must, however, be quite concealed, or it may as well be at home; it is therefore sunk in the ground, and lightly covered with earth and leaves.