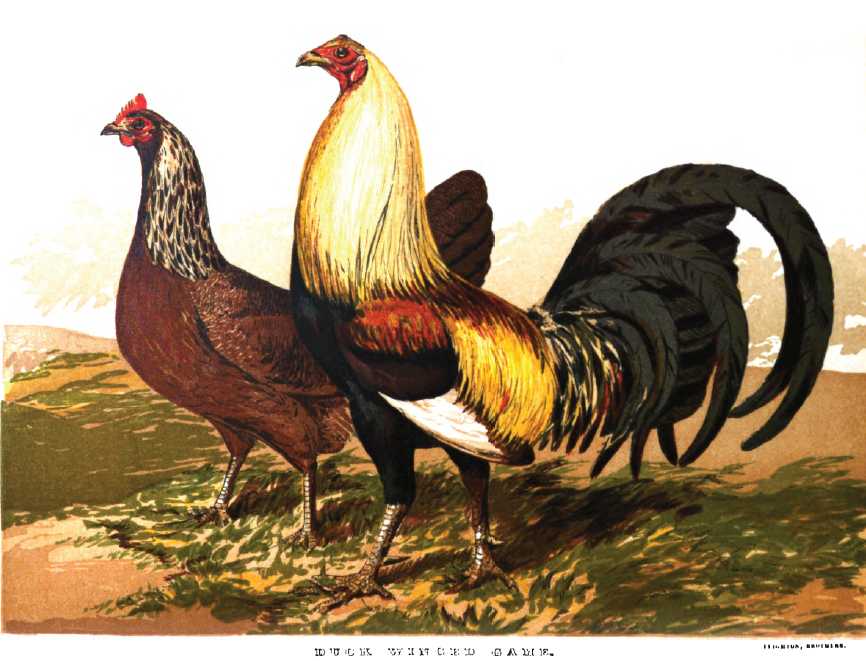

In duck winged game fowl the cocks, to be correct in colour, should have the hackle nearly clear white, with a very slight tinge of straw colour, without any decided yellow tinge or dark streak on the feather.

It may be asked, Where are we to see such birds? I can only say there have been such, and I am in hopes of seeing them again before many years.

The saddle should be as nearly as possible the colour of the hackle; the back a maroon straw; the shoulder coverts a rich brass or copper maroon; the breast and tail pure black.

The hens, to match these cocks, should have their necks of a clear silver striped with black, the silver to go right up to the comb, but being a little darker above the eyes; the back and shoulder coverts, a bluish grey shaft of feather, scarcely showing any difference from the rest of the feather—any approach to red or pencilling is decidedly objectionable; the breast salmon colour, of a nice rich shade.

Duck Winged Game Fowl & Cockfighting

There’s a difference in tone towards the game fowl by the 1867 edition of The Poultry Book. You feel that they’re talking about the birds purely for the aesthetics and the undertones about fighting abilities and courage have, if not completely gone, been toned down.

Cockfighting was legally banned over 30 years before in England and Wales although it was to remain legal in Scotland for nearly another quarter of a century. The problem the breeders have with these birds is that they have been formerly selected for aggressive traits. Cockerels have to be kept apart or inevitably fights to the death will happen.

In nature, when two males fight the norm is for the loser to retreat and the winner to allow this. The loser gets a chance to fight and breed another day and the winner avoids an injury or further injury that may well prove fatal from infection in the following days.

Only by our breeding have we changed nature in these birds and also in some breeds of dog to benefit a sick desire to be entertained by a bloodsport.